Sculptor, Sculpture, and Sacrifice (Ray Charles, T. S. Eliot, and art)

On one of my days off, I was able to bike a Divvy to see the Charles Ray’s sculpture exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago. He is a Chicago-born, Los Angeles-based artist with 19 sculptures currently displayed at the AIC’s modern wing. His works are significant because they are the first solid, machined aluminum and stainless steel sculptures by an artist.

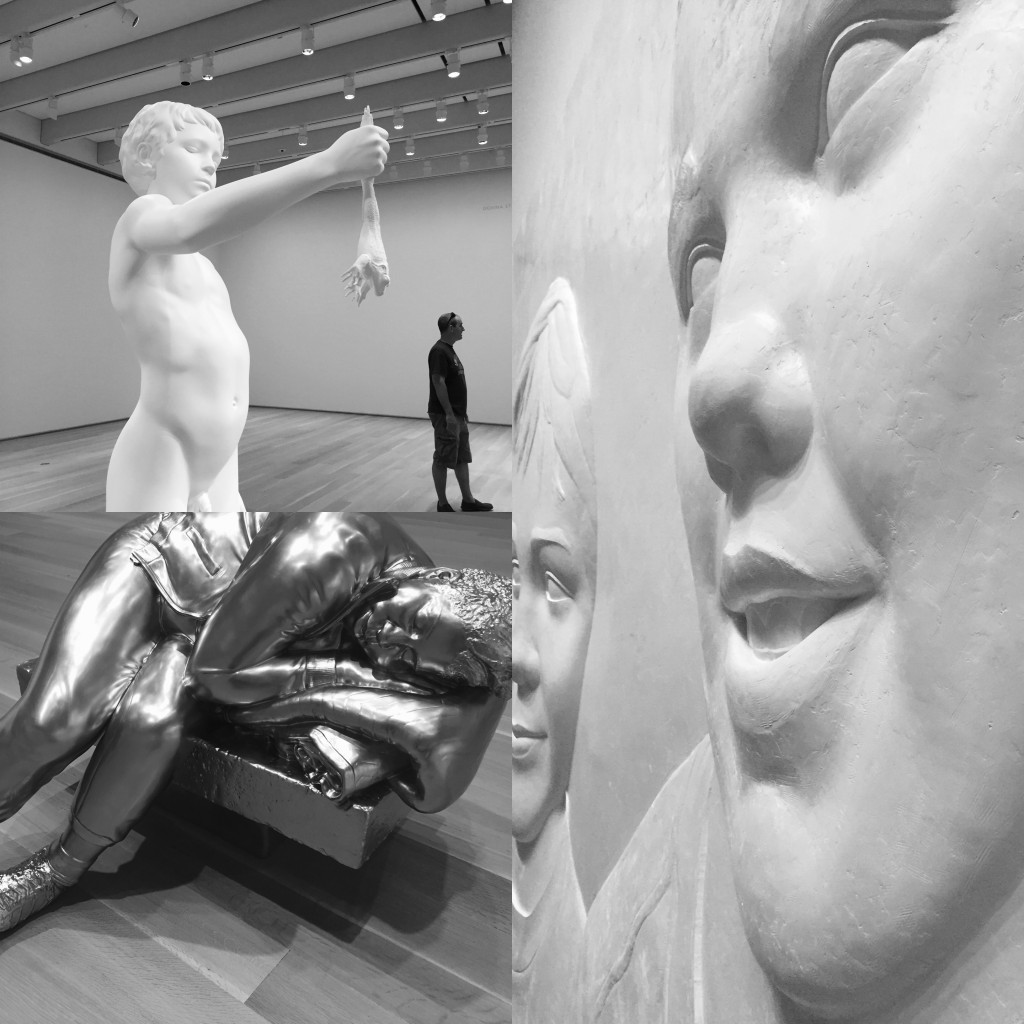

When you enter the gallery, you see an enormous room of space given to each work. Then, when you come up close, you see a remarkable use of materials: aluminum that evokes metal and engineered qualities, yet at the same time looks fluid and organic. For instance, in Sleeping Woman (2012) or Shoe Tie (2012), the work is made of solid stainless steel. The metal infers to us that the subject is cold, hard, and heavy. But because the work is figurative (a shift back from decades of modern abstraction) we feel them as human. Moreover, the reflective qualities have a two-fold purpose: 1) to give a soft and animated energy in contrast to our predispositions (bike frames, plane parts), and 2) to project back the human figures that project humanness upon it!

It was an overall a great exhibit and a real treat. The other works also reference back to Classical sculptures (marble-like material, Contrapposto stances, etc). These works in addition to some surprising bass reliefs made me think about the exhibit as a whole. His innovative materials and modern reproduction of classical subjects remind me of other contemporary aesthetics that our culture is obsessed with:

- The cutting-edge mechanical aesthetic and minimalism of Apple hardware design

- The disruption caused by modern technology so advanced it becomes organic (T-1000 Terminator!)

- The digital surface and in particular Google’s “material design” language about shadow and light

- The illusion of the auteur theory (We like movies often times because of the director’s name)

The last point I will discuss briefly. In many of Ray’s work, he is more like a director. He presides over a variety of engineers, artists, and producers of materials. Many of the subjects he finds, he records, then takes a crew to help him make molds and ship them to other metal or wood working artists to reproduce the subject to the liking of Ray. As much as I like Christopher Nolan or Wes Anderson films, I also still know the names of their actors and actresses (unlike the engineers etc Ray uses to help build his works).

Tradition, Anonymity, and Artists

“You don’t know what you’re doing when you’re working. I think people think it’s an idea that you follow through on, but it’s isn’t, it’s more direction that you go. And then I start chasing the sculpture, trying to wrestle it into existence.”

“Good work of great art is anonymous, it joins a kind of authorship of an age– of a time.”

“Everything I’ve said is going to be washed away, and what’s going to be left is the art part.”

These Charles Ray quotes from the AIC’s youtube video immediately struck me as reminiscent of T.S. Eliot’s essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (1919), a piece I read a long time ago in college! This essay was written by T.S. Eliot emphasizing (one of many points) that when an artist creates a work, he is innovative but at the same time drawing from all the works of the tradition before him/herself. (“What happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art that preceded it.”). This echoes to the “authorship” that Ray states his work “joins.” An artwork is never meaningful alone but always in relationship to other works of art.

Moreover, Ray also mentions a kind of anonymity when an artist creates a work. At the same time an artist creates a work— as it changes the way we see previous and contemporary artworks— the artwork starts to outlive the artist. The act of creation, in seconds, the artwork becomes independent of the artist. Years later, the artist is not as remembered as the artwork itself. This is similar to T. S. Eliot’s “Impersonal Theory.” At one point he states,

What happens is a continual surrender of himself as he is at the moment to something which is more valuable. The progress of an artist is a continual self-sacrifice, a continual extinction of personality.”

Sculptor, Sculpture, and Sacrifice

A lot of discussion can be made if an artwork truly outlives the artist. There is continual exploration/deconstruction of the line between artist and art. But in the scope of this article, I simply point out a poet and sculptor making fascinating claims about art-making. The particular claim that piques my interest is: Why do both artist mention an element of sacrifice in art-making?

If we take God as the being who made us— then He is the artist and we are his artwork. If an artist is someone who makes a “continual extinction of personality,” who becomes “anonymous,” who undergoes a “continual surrender” of the self, then how much more beautiful and meaningful that becomes when it parallels the character of God who is said to have become a sacrificial lamb sent to death to bring us to life. Thus, we— humans— are what Ray calls the “art part” or what T.S. Eliot calls the “something which is more valuable.”

Parallels can be made about identity, image, likeness, and sacrifice when comparing God, T. S. Eliot, and Ray. Just as aluminum is reflective and recursory, the material of God’s art, words and verses both create and at the same time mirror: “Let us make man in our image, in our likeness.” God’s material is words and his art is us. But in order for us to become complete— for the art to become complete— the artist must sacrifice, just as God sacrificed:

Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.

But why sacrifice? He needed to sacrifice a part of Himself in order to complete us and make us alive into a relationship with Him. Perhaps all artists are mirroring this. Art-making is a ritual. With every brushstroke, with every shape we mold with our hands, life is taken from us; yet in this paradox, we create something more— we create something alive. Like an aluminum bell ringing, the theme of surrendering in sculptor, sculpture, and sacrifices echoes again and again with every new artwork. An artist can create art, but an artwork that is alive and relational— that artwork was made with sacrifice.

1. AIC website (http://www.artic.edu/charles-ray-sculpture-1997-2014)

2. T.S. Eliot’s Tradition and the Individual Talent (http://www.bartleby.com/200/sw4.html)

3. Philippians 2 (https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Philippians%202&version=ESV)

Leave a Reply