Hiya: Saving Face, Anxiety, and Asian-Americans

Hiya: Saving Face, Anxiety, and Asian-Americans

“Wasn’t he Filipino?” Jisoo asked as we walked in.

“He might be. Southeast Asian at least. We’ll go and ask him if things go well,” I replied.

For the past few weeks, Jisoo and I have been looking for a new car. After visiting a few dealerships and obtaining quotes we went back to the dealership that had a sales rep guy we really liked. He promised he would match any price we found.

When we entered, from the distance, a familiar baldness twinkled as a head turned immediately to meet us— it was our sales rep guy waiting for us at the door! He gave a cordial greeting then sat us down to begin business. Armed with internet prices, emails, and prior research we bargained through a few quick bouts with him and his manager. As we negotiated, I channeled memories of my dad haggling his way through his first few years in Chicago— loud and heavy-handed— brandishing a frankness only a fresh-of-the-boat immigrant could have.

Like an attending doctor taking charge, the manager started overtaking the sales rep guy in the conversation. The boss would lurch his bony face forward, firm his voice, and iterate a sharper argument as we discussed specifics. After more rounds of back and forth they took a minute away to deliberate apart from us. The sales rep guy came back ready to shake my hand.

“It’s done!”

His face cheesed accomplishment. As I shook his hand I noticed a stubby finger— a healed scar— and his skin was just as brown as mine.

They agreed to come down to our price. We sat back down, and as he moved to the other side, I heard something drop on the floor— a plastic thud— and the rattle of pills inside. I peeked down reflexively and before he hid it back in his pocket, I recognized the brand name— Ativan. He shuffled back to his seat.

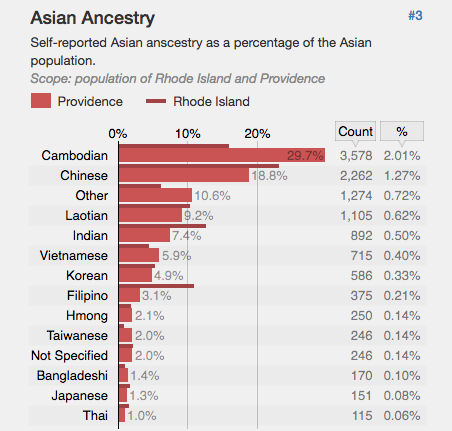

We chatted freely now that the pressure was off. Since we had to disclose our incomes and occupation, he asked us about what it was like being doctors. I shared how I wish I had Filipino patients, but found a lot of enjoyment finding common ground with the Asian patients that I do see. He explained that there was a decent community of Filipinos in the state. There’s also a big population of Hmong nearby, and an even larger population of Laotians.

“And what ethnic background do you come from?” Jisoo asked.

“Cambodian. We immigrated here when I was five as refugees. Lived here ever since.”

We talked about sticky rice, Ali Wong, and the difference between “Fancy” and “Jungle” Asians (my wife is Korean), and where the refugee communities started and how they migrated throughout New England.

§

Our turn was done with him, so we moved on to the finance guy in a separate room. He was an older man who sat up straight. He would speak loud and clear and as his arms waved during talking you would see the glisten of his large golden watch.

After more negotiations of a lesser degree, between the curt flipping of pages, he interjected, “Where is Paul? He should be here.”

He made a quick scan into the dealer room— a greasy glance— then returned back to the contracts.

“He’s probably scared of you— you guys being doctors and all.”

§

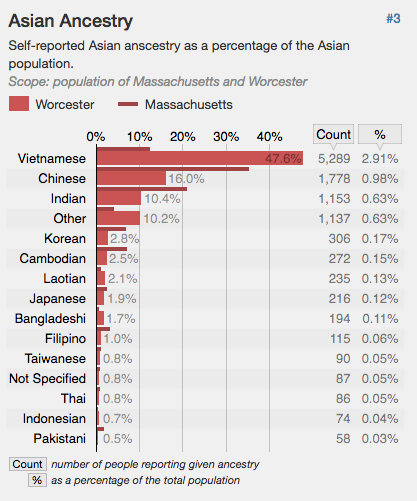

According to Statistical Atlas, in Providence, RI, of people who have Asian ancestry: 39,7% were Cambodian, 18.8% were Chinese, 9.2% were Laotian, 3.1% were Filipino, and 2.1% were Hmong.

A study from the APA from 2008 measured anxiety of a group of college students. The researchers found significant differences, showing Asian-Americans reported greater total social anxiety and distress in new situations than did European-Americans. The researchers suggest that culture may correlate to anxiety differences: “An awareness of one’s inaccuracies in perceiving emotions of others may exacerbate fears of social situations, especially when attunement to others and the avoidance of loss of face are valued.” Moreover, an umbrella analysis from 2017 of several systematic reviews about refugee mental health showed that “anxiety was at least as frequent as post-traumatic stress disorder, accounting for up to 40% of asylum seekers and refugees.”

§

As a family physician, I am privy to all kinds of experiences my patients live through day by day. Last week i had a prolonged discussion with a patient about starting benzodiazepines (like Ativan) or not. The patient had an unexpected death in the family, a stressful home life, and a job as a PCA which exacerbates her social anxiety. I ended up giving her benzodiazepines.

Filipinos have a cultural attitude called “hiya” which roughly translates to “embarrassment,” “shame,” or “saving face.” It’s a painful emotion realizing one has not met up to society’s standards. “Mapahiya” is intentionally acting towards others that avoids causing another person to feel embarrassed. Other cultures have similar ideas, such as “saving face” (Miànzi, 面子) in China or “to lose face” (mentsu wo ushinau, メンツを失う) in Japan. These values often can be problematic to the American values of individualism and non-conformism. This often came up when I watched movies when I was young. When an embarrassing thing happened on screen to a character and I would suddenly feel flushed and red as though I myself was embarrassed!

Doctors have a sense of hiya. Hiya— feeling embarrassed when another person is embarrassed— is in a way, a practice of empathy. We hear what our patients say and feel what they are going through so that we can help them. With the modernization and computerization of medicine, we are now realizing the importance of training doctors in empathy.

As I think about the car sales rep, my patients, and my self— as I think about the current opioid and benzodiazepine epidemics— as I think about refugee and minority healthcare— that drop of a plastic pill bottle rings in my head. I pray that whether I see people in clinic, on the street, or even in a car dealership, that I try to see them as a whole person. When I look into a stranger’s eyes, I pray for a larger heart— so that I can hold their story, their daily struggles, and the deep yearnings they may hide in their pockets.

At the end of that day, we went home wondering how he was treated by his colleagues at the end of the day, what cheers or jeers were said, his drive home, what he ate for dinner, his next doctor appointment, and if pills eased the sores that we partook in reopening.

§§§

- Turrini, G., Purgato, M., Ballette, F., Nosè, M., Ostuzzi, G., & Barbui, C. (2017). Common mental disorders in asylum seekers and refugees: umbrella review of prevalence and intervention studies. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11, 51. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-017-0156-0

- Lau, A. S., Fung, J., Wang, S.-w., & Kang, S.-M. (2009). Explaining elevated social anxiety among Asian Americans: Emotional attunement and a cultural double bind. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(1), 77-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0012819

- Lasquety-Reyes, J. (2016). In Defense of Hiya as a Filipino Virtue. Asian Philosophy, 66-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09552367.2015.1136203

- Hemmerdinger, J., Stoddart, S., Lilford, R. (2007) A systematic review of tests of empathy in medicine. BMC Medical Education 7:24 https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-24

- Statistical Atlas – Worcester, MA

- Statistical Atlas – Providence, RI

- Fancy and jungle asians – by Off the great wall (youtube video)

Leave a Reply