Examining Princess Mononoke: Death, Medicine, and the Direct Address

What makes a person not waver in front of death?

One of the best parts about movies, literature, and art in general is that you can rewatch/reread them and always learn something new. The movies I’ve watched before can feel like brand new encounters because the experiences I’ve had since then now reframe movies in a new context. Moreover, rewatching old movies reframe my perception and even comment on my recently acquired experiences!

Outline:

Princess Mononoke

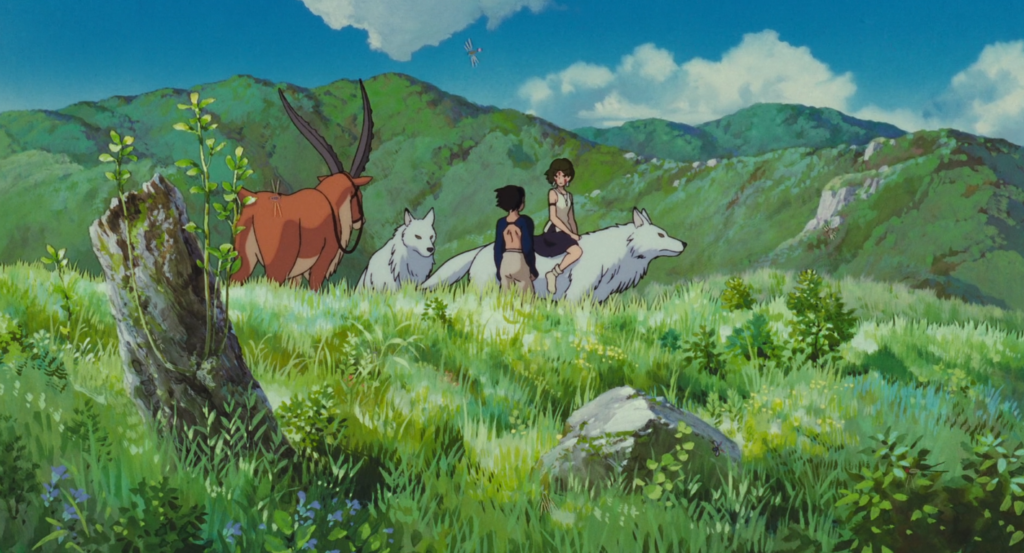

I recently rewatched Princess Mononoke and fell in love with it again. Princess Mononoke is a 1997 Japanese anime film written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki and animated by Studio Ghibli. It is a story about Ashitaka, a young man from an isolated village who is cursed when fighting a demonic boar. He leaves his village to seek out a cure for the curse and stumbles into Japan’s multiple warring states— all struggling for power and land. In particular, he meets a group of former prostitutes and lepers led by a passionate woman, Eboshi, who wants to control the forest to obtain iron. He entangles himself in their fight against the animal spirits of the forest who are led by the Deer God, a wolf clan, and a wolf-girl, San.

When I first saw the film, it must’ve been when I was in middle school. I’ve rewatched the film several times since then and always found it’s themes so poetic and meaningful. Now that movies are trending towards themes about environmental stewardship (Avatar, WALL-E), representation of minorities (Black Panther, Crazy Rich Asians), and strong female leads (Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Mad Max: Fury Road), Princess Mononoke becomes all the more impressive for being ahead of its time.

Environmental stewardship

Saving the environment was the first and strongest theme that impacted me when I was young. Anime is first of all, a visual impression, and the film’s treatment of nature takes advantage of that. There are ample long-shots and panoramas of Japan’s landscape: mountainsides covered with forests, primordial groves of holy ambience, plains and rice fields stretching over rolling hills. These scenes impress on us a natural beauty in contrast to other scenes of warring samurai, violence, and the fires of industry.

Studio Ghibli’s painterly scenes combined with Japanese cinema’s patience in letting us meditate on a single shot pays off. While Western films may not linger on a shot for too long for fear of losing the audience’s attention; the film stands its ground. Moreover, the emotional climax and redemption of the story is mirrored by the aesthetics of nature— which are all given copious amounts of screen time: when the Deer God is killed, the forest is reduced to decay and death; when the apocalyptic land is redeemed, the landscape is visually transformed into sprouts and new growth.

Cartoons like Captain Planet, The Magic School Bus, and films like Avatar paint similar themes about conserving the environment and its natural goodness and wonder. In these films, there is an obvious antagonist to nature that is often caricatured. For example, in the Avatar film, the figurehead of the mining corporation on Pandora is Parker Selfridge. The film’s treatment of him is mostly of vilification: “What the hell have you people been smoking out there? They’re just god-damn trees!” Despite Selfridge eventually showing some hesitancy and remorse; like the villains of Captain Planet, films treat environmental villains as mostly one-dimensional.

In Princess Mononoke treatment of antagonists to nature is significantly different. Lady Eboshi wants to destroy the forest and conquer the animal spirits to obtain the iron but does so to give jobs to and empower the vulnerable— former prostitutes and lepers. People need to work and live, and resources are needed for this. This is true in real life as well. In the States, conversations about coal and oil versus renewable energy are complex and tied to culture and identity (as most things are). In real life, there are few caricatures of evil villains, rather more people like Eboshi.

Ashitaka: First you steal the boar’s forest from him, then transform him into a demon. Now you’re making even deadlier weapons. How much more hatred and pain do you think we need?!Eboshi: Yes, I’m the one who shot the boar. And I’m sorry you suffer I truly am. That brainless pig… I’m the one he should have put a curse on, not you.

One could venture to a Marxist and Environmentalist analysis at this point, but I think this should suffice. I would summarize by saying that this conversation being possible is in many ways why Princess Mononoke is so more mature than Avatar, FernGully: The Last Rainforest, or WALL-E.

Female leads and complex characters

San is a female lead who has her own goals and desires. I find it refreshing that her purposes don’t get steamrolled when Ashitaka enters her life. Yes, she is saved by Ashitaka multiple times. But she also saves the protagonist multiple times in turn. The way the film treats their relationship is so respectful and genuine that I can’t imagine many equatable pairings in movies (Max and Furiosa from Mad Max: Fury Road comes close). As a young middle school boy, I knew there was something so cool and so mature about her that only as I grew up that my respect for strong female leads became intelligible.

Eboshi is an incredibly complex character. One of the most effective turns in the movie is when the audience is led to go back and forth about our empathy for her. She seeks to destroy the forest and conquer the animal spirits living there. The film later reveals she buys out prostitutes from brothels and employs lepers to empower them through iron making. She makes guns and weapons of destruction. She is often in the front lines of battle. She is indomitable in her will. She is the first to repent in the end when iron works is destroyed. One of my favorite lines from her highlights her singular spirit and sincere belief in empowerment when she learns samurai are attacking Irontown while she is away: “The women are on their own now. I’ve done all I can for them. They can take care of themselves.”

The spirit animals are shown to be giant, sentient, and complex characters themselves. They have their own desires that even conflict with other animals of the forest. Okkoto, the leader of the boars, is a character who is shown to be courageous, especially in battle, but strong-willed to the point of being heedless. His physical blindness correlates to his inner nearsightedness to the consequences of his passions. Okkoto seeks the Deer God to help his cause but fails to see that he will lead the enemy to their goal: “If you are lord of this forest, revive my warriors to slay the humans.” This exclamation is after Moro, the wolf God mother, explicitly reminded Okkoto that “The Forest Spirit gives life and takes life away. Life and death are his alone, or have you boars forgotten that?”

Life and death

Environmental stewardship and complex female characters are now themes I and a growing number of moviegoers now intentionally seek. A newer theme that has become more relevant to me on rewatch is that of life and death. For this last part, I want to talk about how Princess Mononoke treats death through the Deer God and what that means for the audience and for me personally.

Becoming a doctor has let me be privy to some of the most intimate and singular experiences humans undergo. As a family doctor, I get to share in the joy of a newly delivered baby, help people persevere through the daily aches and pains of life, and even guide people to the end of life. Some of my most formative encounters of the human condition involves withdrawing care to a terminally ill person, performing CPR and resuscitative codes, and declaring death.

In the hospital, I often see patients getting so sick to the point that medical interventions become non-beneficiary and even harmful. Sometimes we intubate patients and support them with a breathing machine but later find out they never wanted to live like that. Do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders are a prior decision made by the patient to withhold CPR when the intervention will not benefit the patient. Ideally they are made before a person becomes critically ill. However, when “DNR order discussions do occur, they frequently occur too late. A study of 500 patients who suffered from a cardiac arrest showed that 76% of these patients with DNR orders were incapacitated to make decisions at the time a DNR order was discussed. However, only 11% were impaired at the time of admission.”(1)

When a patient decides to withdraw intensive care and pass away or decides beforehand to have a DNR, DNI, or CMO status, they have to fully realize the stakes and the consequences of their actions and be at peace with that decision. Sometimes, I see people who, with very reasonable insight, have end-stage COPD or cancer or some terminal disease that at first are DNR/DNI but when the moment comes— when the feelings of suffocation or pain come— they revoke the DNR/DNI and have us intervene.

How the characters respond to death

What makes a person not waver in front of death? I believe those patients who can sustain their DNR/DNI have a peace with their decision— and their peace comes from a resolve of the truth and a surrendering to that truth in their hearts. Look at this exchange in the beginning of the movie, when Ashitaka learns that he will die:

Matriarch oracle: My prince, are you prepared to learn what fate the stones have foretold you?Ashitaka: Yes, I was prepared the very moment that I let my arrow fly.Matriarch oracle: Mmm. The infection will spread throughout your whole body, bone and flesh alike. It will cause you great pain and then kill you… You cannot alter your fate, my prince.. However, you can rise to meet it, if you choose… There is evil at work in the land to the west, Prince Ashitaka. It’s your fate to go there and see what you can see with eyes unclouded by hate.

In another scene, Ashitaka is shot while saving San. San takes him to the forest and the Deer God saves Ashitaka’s life (but does not lift his curse). On their way to kill the humans, Okkoto and the boars have a conversation with Ashitaka and the wolf tribe. The boars find out the Deer God saved Ashitaka but not Nago, a fellow spirit boar who was killed by the humans.

The boars: The Forest Spirit saved him (Ashitaka)? Saved the life of that loathsome runt? Why didn’t he save Nago? Is he not the guardian of the forest? Why?Moro: The Forest Spirit gives life and takes life away. Life and death are his alone, or have you boars forgotten that?The boars: You lie! You must have begged the Forest Spirit to spare his life! But you did not beg for Nago, did you?Moro: Nago was afraid to die. Now I, too, carry within my breast a poisoned human bullet. Nago fled, and the darkness took him. I remain and contemplate my death.San: Mother! Please ask the Forest Spirit to save you.Moro: I have lived long enough, San. Soon the Forest Spirit will let me rest forever.San: All these years you defended the Forest Spirit! He must save you!The boars: You are not fooling us. Nago was beautiful and strong. He would not have run from anything. You wolves must have eaten him!

The boars’ avoidance of the truth is a substantial contrast to Moro’s acceptance of the truth. Moro knows the reality that the time of God spirits will die and humans will take over. The forest will change and Moro surrenders to that truth. The boars’ leader, Okkoto, ends up with the curse that Ashitaka and Moro suffer and he presents a contrasting reaction to that reality: “If you are lord of this forest, revive my warriors to slay the humans.” We are not surprised to see his strong-willed nature corrupt him into a demon and aide the humans in finding the Deer God as Moro predicts, “Okkoto’s too stubborn. He won’t listen. None of them will. They may even know it’s a trap. The boars are a proud race. The last one left alive will still be charging blindly forward.”

Ashitaka and Moro (and to an extent Eboshi), are like my patients who do not revoke their DNR/DNI status when death is approaching, they have clarity of their fate and a peace in their hearts with that reality.

Is this the moral of the story? That we shouldn’t allow pride or hate blind us from the truth? That when death comes we should accept it and be at peace rather than run away or deny it? Is this the meaning of seeing with “eyes unclouded?”

I do not think the film treats the theme of death so simply, nor chooses to bank its work and heavy-lifting into the device of morals that we should learn or cautionary tales. In real life and in the hospital, it isn’t that simple either. Telling patients to just accept that interventions are futile and to accept death’s inevitability as a fact does not work (I know because I’ve seen others try, myself included).

The Deer God and death

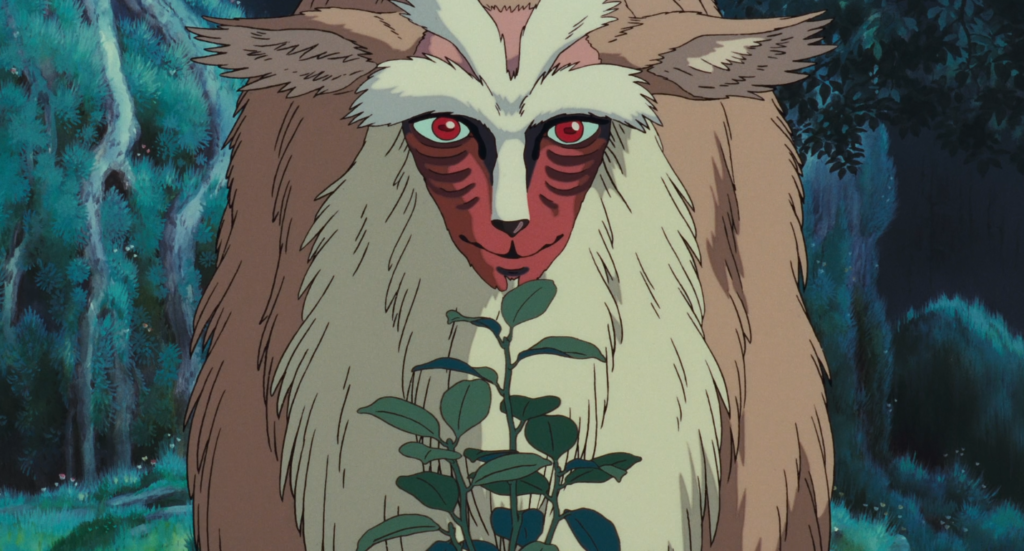

Let’s look at another character who dies: the Deer God. When I rewatched the movie again, I realized I’ve never closely looked at the function of the Deer God in relationship to the other characters. The Deer God (also translated as The Forest Spirit,) comes from Japanese words Shishigami (シシガミ) and Daidarabotchi (Night-Walker, ヂダラボッチ). Daidarabotchi are giant spirits that shape the land as they travel.(2) The Deer God has the power to heal, save life, and the power to cause death. In the film, we see the animal spirits and humans seeking power from the Deer God.

The Deer God says no words the entire film. He has the body of a deer and a face of a human with tree-like antlers. At night he becomes a giant, ghost-like humanoid. The Deer God also has a kind of omnipresence in which he is aware of all those around him. When Ashitaka sees him for the first time, while the protagonist strains to see him, the Deer God appears to gaze at Ashitaka well and directly. When Eboshi aims her gun sight on the Deer God, he gazes back knowingly. When the Deer God intends to heal characters, there is always a shot of his face— prominent and centered in the camera’s frame.

In all these shots, the film takes a few seconds for us to gaze on his face as well. By taking more time with these direct close-up shots of his face, we gaze upon his eyes. There is something meditative and transformative going on here and it involves the audience.

When Ashitaka first sees the Deer God:

When Ashitaka is healed by the Deer God:

When the Deer God comes to heal San and Okkoto but is first shot by Eboshi (Notice how the Deer God looks at the audience before and after being shot):

Before Eboshi fires a second shot and kills the Deer God, notice that the Deer God looks at her and the audience again:

San and Ashitaka give back the Deer God’s head:

The movie uses the Deer God as the ultimate God and redeemer of the story very similar to the figure of the Christian Christ. It is inconsequential if the writers or animators intentionally made him a Christ-figure (see Reader-Response Criticism).(3) They chose an ultimate God-head figure to willingly die in the story and through his death heal people and redeem the land. Narratively, emotionally, and structurally the story needs a figure who surrenders to death but through that death brings redemption and life. When Moro died, there was no redemptive power. If Ashitaka or San died, I suspect it would not have brought about a redemption as the Deer God’s death did bring.

I recently read an article from Poetry Foundation in which John Barr talking about what can break America away from the stagnant poetry of today:

“Groundbreaking new art comes when artists make a changed assumption about their relationship to their audience, talk to their readers in a new way, and assume they will understand. When Melville wrote, “Call me Ishmael”; when Whitman wrote, “I celebrate myself and sing myself, / and what I assume you shall assume”; when Baudelaire wrote, “Hypocrite lecteur”; when Frost, in the first poem of his first book, said, “You come too”: each seemed to make transforming assumptions about his audience. Their direct address was address made somehow more direct. It held, succeeded, and literature was changed.”(4)

The film uses the “direct address” through the explicit gaze of the Deer God to the audience. Remember that the Deer God never speaks, yet there is this feeling of a transaction. Using no language but an explicit gaze implies the film wants to say something deeper than language. What happens when the Deer God gets shot the second time? He turns his neck to look at Eboshi and then us, the audience. The film is directly asking us to resolve our own truths and to surrender to our own beliefs about death.

In real life, it is taboo to talk about death and dying, but it is something every single person will go through. In medicine, we have to talk about it. A BMJ article from 2012 gives doctors some tools to talk about death directly to patients. In that article they mention “Reluctance to talk openly about dying and death is a significant barrier to improving access to end of life care and advance care planning.” A survey in Britain “found that only 27% of the public have asked a family member about their end of life wishes and less than a third (31%) have talked to someone about their own wishes… a third (35%) of GPs have not initiated a discussion with a patient about their end of life wishes.”(5)

Okkoto and Moro differ in their last moments of life, but the Deer God gives them both peace in the end. Above all, the Deer God desires peace and life for all living things. It comes at a sacrificial cost, but the Deer God is above life and death. After the Deer God sacrifices himself and redeems the land, San and Ashitaka have an exchange:

San: The Great Forest Spirit is dead now.Ashitaka: Never. He’s life itself. He’s not dead, San. He’s here right now, trying to tell us something, that it’s time for us both to live.

The conversation ends with Ashitaka looking at his hand which is healed from the curse. The frame of the camera centers his hand with the extension of that arm as if coming from our own real-life bodies. The “us” that Ashitaka refers to now extends from the characters on the screen to us, the people in the audience— to me and to you. This is the “direct address” that John Barr says makes art transformative.

How do you accept the reality of your own death and be at peace? The film posits that it requires a “direct address” by a Christ-like God whose surrender to death brings about a redemption of life. The Deer God surrenders to death to teach us to surrender to death in our hearts. This is the “something” the film is “trying to tell us.” The film explicitly is tackling our fears we have with death and our reluctance to face it.

I’m not saying that we should look at Princess Mononoke as a religious text or automatically adopt the morals that art or stories feed us. But I do think art can be direct with us. My personal beliefs and worldview assumes that a text can literally change someone’s heart and soul. I think when a text treats me explicitly there will be a transformative change in how I view it and consequently the world. Language is a difficult transaction, but we know that art can change our opinions and grow our empathy.(6) What is this mechanism and can we expound on it? Can we experiment and see if art can make a direct conversation with us and possibly engage with our beliefs— even of life and death?

§

You have said, “Seek my face.” My heart says to you, “Your face, LORD, do I seek.” – Psalm 27: 8 English Standard Version (ESV)

“The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.” – Job 1: 20-22 English Standard Version (ESV)

“I came so that everyone would have life, and have it in its fullest.” – John 10: 9-11 Contemporary English Version (CEV)

§§§

- Yuen JK, Reid MC, Fetters MD. Hospital Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders: Why They Have Failed and How to Fix Them. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26(7):791-797. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1632-x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3138592/

- Meyer, M. (2018). Daidarabotchi. Retrieved from http://yokai.com/daidarabotchi/

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018, May 10). Reader-response criticism. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 02:13, May 30, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reader-response_criticism

- Barr, J. (Aug, 2006). American Poetry in the New Century. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/articles/68634/american-poetry-in-the-new-century

- Wise J. Dying remains a taboo subject for patients and GPs, finds survey. BMJ. 2012; 344 :e3356. https://www.bmj.com/content/344/bmj.e3356.full

- Blunt, T. (2016). This is How Literary Fiction Teaches Us to Be Human By. Retrieved from http://www.signature-reads.com/2016/09/this-is-how-literary-fiction-teaches-us-to-be-human/

Leave a Reply to Mousami Cancel reply